- The LegCo Complex

- Facilities of the Complex

- Plan a Visit

- Guided Tour

- Virtual tour of LegCo Complex

- Souvenir Shop

- Getting Here

- Security screening arrangements for admission to the Legislative Council Complex

- Note for the public attending or observing meetings

- Guidelines for staging petitions or demonstrations

- Contact Us

Mosquito prevention strategies |

ISE32/20-21

| Subject: | environmental hygiene, diseases control and prevention, mosquito prevention |

- Mosquito bites can cause more nuisance than itchy and annoying feelings. Mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue fever ("dengue"), Zika virus and malaria may pose public health threats, even in developed places.1Legend symbol denoting Diseases such as dengue fever ("dengue"), Zika virus and malaria are spread by infected mosquitoes, with more than 700 million infections and one million deaths recorded annually worldwide, according to some estimates. Developed places are not entirely free from outbreaks of such diseases, as observed in the spread of dengue in parts of Portugal in 2012 and an increased number of cases in Singapore in 2020. See World Mosquito Programme (2021a) and World Health Organization (2021). Hotter and wetter weather arising from climate change may prolong mosquito seasons, and thus more persistent effort in tackling the problem is required.

- Most (sub)tropical places in Asia-Pacific, including Hong Kong, are home to Aedes mosquitoes, a type of mosquito known for spreading diseases like dengue and Zika virus. Some mosquito surveillance data indicated that the prevalence of such mosquitoes in Hong Kong may have become higher over the years. Meanwhile, the number of dengue cases rose from 43 in 2009 to a record of 198 in 2019, even though the illness is far from being considered epidemic in Hong Kong, with most cases being imported.2Legend symbol denoting While mosquito-borne diseases like dengue and Zika virus are not spread directly from human to human, vector mosquitoes may carry these diseases from an infected person to another. Currently, there is no specific medication for dengue and Zika virus. In Hong Kong, there are neither effective vaccines against dengue nor Zika virus and malaria. It should be noted that there were significantly fewer dengue cases in 2020, in part attributable to less imported dengue cases due to COVID-19 travel restrictions. See Centre for Health Protection (2019 and 2021). Mosquito prevention thus remains a concern for Legislative Council Members.3Legend symbol denoting See GovHK (2016 and 2018). The Panel on Food Safety and Environmental Hygiene has been discussing the issue annually. Recently, the Office of The Ombudsman ("Ombudsman") has completed an investigation on the effectiveness of local mosquito prevention and control programmes.

- Traditionally, mosquito prevention and control efforts involve deploying traps to sample the mosquito population to enhance surveillance, and controlling mosquitoes by chemical means or source reduction of potential habitats. Over the past decade or so, some places have begun trying alternative methods to combat mosquito growth. This issue of Essentials reviews anti-mosquito strategies in Hong Kong, followed by a discussion on relevant measures in selected cities on the Mainland, in Singapore and Australia in terms of (a) building smart surveillance systems and enhancing dissemination of information (in terms of frequency and details) on mosquito prevalence; (b) harnessing mosquito control innovations; and/or (c) raising public awareness of and participation in mosquito prevention.

Mosquito prevention in Hong Kong

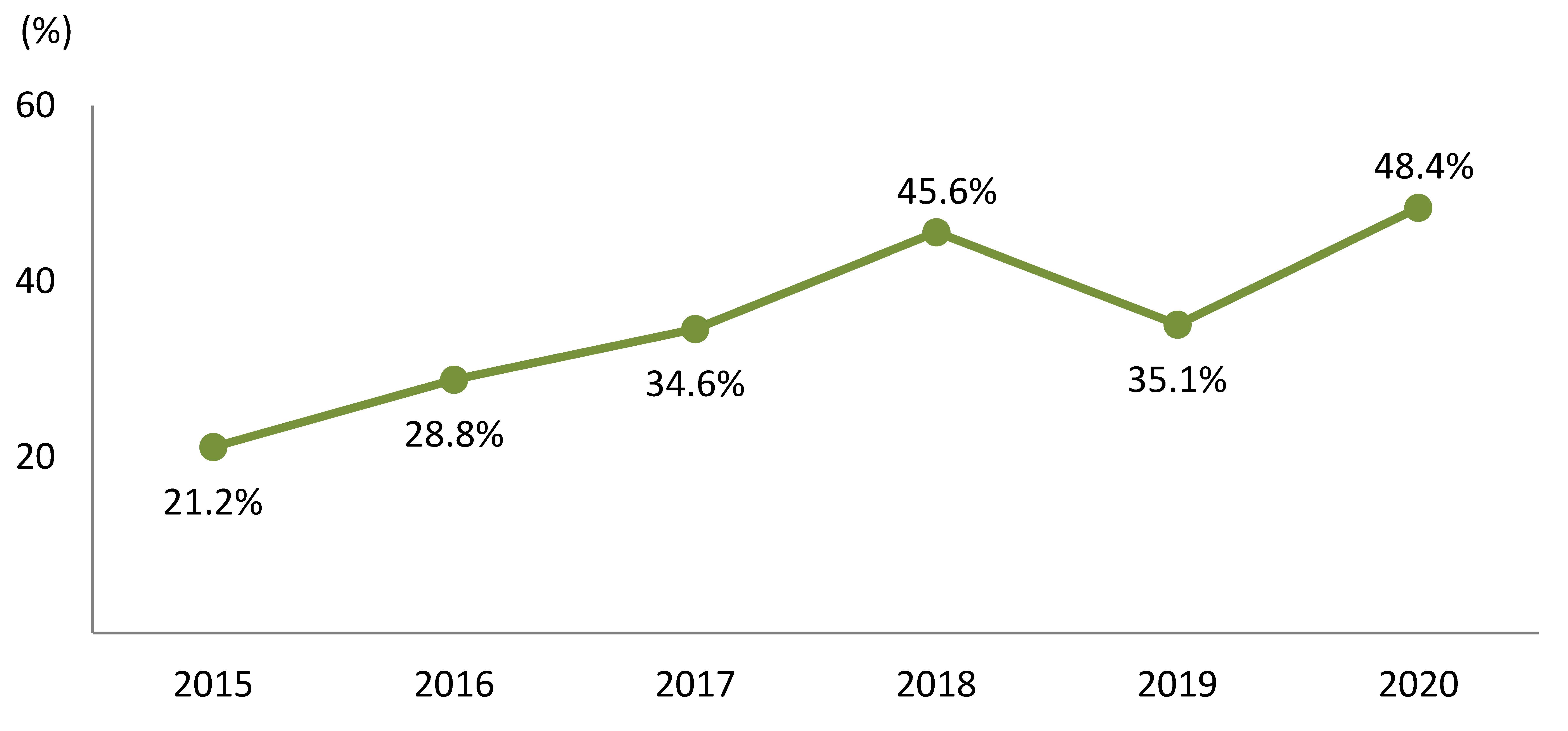

- In Hong Kong, the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department ("FEHD") plays a leading role for anti-mosquito work, which comprises both surveillance and control. On mosquito surveillance, FEHD has put in place 3 440 gravidtraps (formerly ovitraps)4Legend symbol denoting Since April 2020, FEHD has replaced ovitraps with gravidtraps for more timely surveillance due to simplified procedures. When asked by Members at a meeting of the Panel on Food Safety and Environmental Hygiene in 2020 about the criteria for selecting locations for setting up ovitraps/gravidtraps in the survey areas, the Government replied that FEHD's pest control staff would identify places with higher human concentration and potential for becoming a mosquito breeding ground. See Legislative Council Secretariat (2020) and Office of The Ombudsman (2021). in selected areas to monitor the prevalence of Aedes albopictus (an Aedes mosquito species). As at April 2021, gravidtraps have been placed in 64 survey areas. FEHD also publishes on its website the gravidtrap index to show the extensiveness of the distribution of Aedes albopictus in each survey area over the past month.5Legend symbol denoting The Gravidtrap Index is expressed as a percentage of gravidtraps found positive with breeding with Aedes albopictus. Every month, FEHD issues a press release to highlight to the public the overall gravidtrap index aggregated from all survey areas, as an indication of whether the infestation threat is serious. The index by survey area is called Area Gravidtrap Index ("AGI"). Besides AGI, FEHD has been publishing the Area Density Index ("ADI") since April 2020 to show the density of the Aedesspecies in each survey area. Apart from the 64 survey areas in the community, FEHD carries out mosquito surveys in major port areas. See Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (2021b). The index is divided into four levels from Level 1 (not extensive) to Level 4 (very extensive).6Legend symbol denoting Of the four levels of the gravidtrap index, Level 3 and 4 are "alert levels" that warrant specific preventive measures. Level 3 (20% to less than 40%) shows that the distribution of Aedes albopictus is extensive with infestation exceeding one-fifth of the survey areas. Level 4 (40% or above) shows that almost half of the survey areas is infested with the mosquito species. If an area reports a gravidtrap index at alert level (i.e. Level 3 or above), FEHD will activate its response mechanism to alert relevant Government departments and property management offices to take targeted control measures. In 2020, 48% of the survey areas recorded at least once the monthly indices at alert level, up from 21% in 2015 (Figure 1).7Legend symbol denoting See Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (2021a).

Figure 1 ― Percentage of survey areas with monthly gravidtrap/ovitrap indices exceeding alert levels (≥ Level 3), 2015-2020

Source: Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (2021).

- On mosquito control, FEHD has a team of more than 2 000 in-house and contractor staff tasked with various anti-mosquito duties. Apart from conducting inspections and removing mosquito breeding sites before the rainy season, FEHD uses chemical control methods such as fogging operations and application of larvicidal oil to eliminate mosquitoes once the rainy season begins. The mosquito control work will be stepped up as part of the response mechanism when the gravidtrap index reaches Level 3 or above. In 2020, it was estimated that some 69 000 mosquito breeding sites were eliminated.8Legend symbol denoting See Food and Health Bureau (2021).

- In July 2021, the Ombudsman completed an investigation on the effectiveness of anti-mosquito work in Hong Kong. FEHD responded positively to the Ombudsman's recommendations. Major findings and recommendations of the Ombudsman, alongside public and expert views, are summarized below:

(a) Enhancing mosquito surveillance and providing more user-friendly information: The existing surveillance indices are considered too broad-brush in showing the extensiveness of the mosquito problem. For one thing, the gravidtrap index is released on a monthly basis and is aggregated at district levels for all 64 survey areas, hence may fail to highlight more severe mosquito infestation in certain hotspots (e.g. particular housing estates) within an area.9Legend symbol denoting See Office of The Ombudsman (2021), Legislative Council Secretariat (2020) and 東方日報(2018年). There are calls for expanding the surveillance coverage by placing more gravidtraps in the survey areas, and using timely interactive maps to make crucial information clear at a glance as well as to provide more granular details.10Legend symbol denoting Ibid. (b) Adopting novel, non-chemical technology: There are suggestions that FEHD should seek collaboration with research institutes to enhance the effectiveness of mosquito prevention.11Legend symbol denoting See Office of The Ombudsman (2021) and 香港01(2018年). The need for exploring new technologies also stems from rising environmental concerns over traditional chemical use, as a study conducted by a local university showed that the use of larvicidal oil risked polluting the ocean environment.12Legend symbol denoting See The University of Hong Kong (2020). Moreover, the World Health Organization ("WHO") has warned of potentially waning effectiveness of chemical insecticides arising from insecticide resistance13Legend symbol denoting It refers to the phenomenon that some mosquito species gradually develop resistance to chemical insecticides. See World Health Organization (2015). being developed in mosquito populations, and has encouraged the use of innovative, non-chemical based tools for controlling mosquitoes. (c) Strengthening community engagement: The Ombudsman noted that details of the anti-mosquito response mechanism were only disseminated to the public after it was activated.14Legend symbol denoting For example, it noted that FEHD had not adequately promoted its response mechanism or alerted the public about the implications of the monthly gravidtrap indices. See Office of The Ombudsman (2021). It urged the Government to strengthen publicity of FEHD's surveillance and response mechanism, so as to encourage greater public participation in mosquito prevention work.

Mosquito prevention in other places

- At the same time, places like Beijing and Guangzhou on the Mainland, Singapore, and New South Wales and Queensland of Australia provided examples of more proactive use of new technologies to enhance mosquito surveillance, prevention and control measures as well as programmes to better engage the public, which are outlined below:

Building smart surveillance systems and enhancing information dissemination

- More extensive mosquito monitoring: Located in the tropics where the Aedes mosquitoes could breed year-round15Legend symbol denoting In the first half of 2021 alone, Singapore reported more than 2 700 dengue cases. See National Environment Agency (2021b)., Singapore has built a surveillance system powered by a dense network of Gravitraps. Though smaller than Hong Kong in terms of total land area, Singapore has deployed about 50 000 Gravitraps island-wide to monitor the Aedes mosquito population.16Legend symbol denoting The Gravitrap is spelled differently from Hong Kong's gravidtrap, and is developed in-house by NEA for mosquito surveillance. See National Environment Agency (2019). This extensive deployment has enabled the National Environment Agency ("NEA") to identify mosquito-prone areas more efficiently.

- Multiple channels for information dissemination in user-friendly formats: In recent years, Singapore has made the surveillance data available not only through NEA's website, but also via the agency's mobile application ("NEA app"). Timely interactive maps are also used to help the public visualize locations with high Aedes mosquito population and dengue outbreaks, and to provide more granular level of details (e.g. a specific housing estate/neighbourhood) to suit the needs of individual users.17Legend symbol denoting See GovLab (2016). In addition, the NEA app sends automated alerts on mosquito and/or dengue threats to users based on their location settings for their easy reference.

- Novel mosquito forecast technology: Beijing has leveraged artificial intelligence to predict mosquito proliferation. It has recently developed the Mosquito Biting Index (蚊蟲叮咬指數), which is released on a daily basis during summer months since July 2021. This index is the result of interdepartmental collaboration between Beijing Meteorological Service (北京市氣象服務中心) and Beijing Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (北京市疾病預防控制中心). Using algorithms to analyse parameters such as temperature, rainfall and wind speed over the last decade, the index forecasts mosquito density in five levels and up to three days ahead, so as help the government optimize its response strategies. In terms of information dissemination, the Mosquito Biting index is announced in weather reports on television and social media during summer to give advanced warnings to residents so they can take appropriate preventive measures (e.g. use mosquito repellent and dress suitably).18Legend symbol denoting See 新華網(2021年) and 央視網(2021年).

Harnessing mosquito control innovations

- More efficient inspection and removal of mosquito sites: Like Hong Kong, Singapore emphasizes source reduction as the focus of its mosquito control strategies. For example, households can be fined for mosquito breeding habitats detected in their homes.19Legend symbol denoting Recently, Singapore has raised the penalty for mosquito breeding offences. Effective from July 2020, the penalties range from S$200 (HK$1,147) for the first offence to S$5,000 (HK$28,663) and/or three months in prison for the third and subsequent offences. As for Hong Kong, the maximum penalty on mosquito breeding in one's premises is HK$25,000. See National Environment Agency (2020) and 食物環境衞生署(2021年). While removing and conducting checks on breeding sites can be laborious, NEA has started deploying drones since 2016 to check inaccessible areas such as roof gutters, and increase the efficiency of inspections. Where needed, the drones can dispense larvicide at targeted sites and take photos of the problem spots for requiring home owners to take remedial action.20Legend symbol denoting See Ministry of Transport (2016). In 2020, NEA conducted one million inspections and found 2 400 mosquito breeding sites, compared with 19 000 sites uncovered from 1.4 million inspections in 2015.21Legend symbol denoting Ibid and see National Environment Agency (2021a). Furthermore, 8 100 enforcement actions were taken against owners of mosquito-breeding premises in 2020.

- Alternative method of mosquito control: In recent years, there has been a growing trial of the Wolbachia method as a mosquito control strategy with a view to reducing the use of chemical insecticides. This method involves injection of bacteria – known as Wolbachia – into male Aedes mosquitoes by scientists, without genetic modification. When the Wolbachia-infected males are released to mate with uninfected female ones in the wild, they are unable to produce offspring, thereby reducing the spread of mosquito-borne diseases.22Legend symbol denoting Harmless to humans, Wolbachia is naturally found in 60% of insect species like bees and flies, but not Aedes mosquitoes. The Wolbachia bacteria can be used in various ways, including to suppress mosquito populations with the release of only male Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes. This approach is piloted in places like the Mainland and Singapore, among others. Alternatively, places like Australia and Brazil adopt a slightly different approach that involves the release of female Wolbachia mosquitoes to breed with the wild mosquito population. When Wolbachia-infected female mosquitoes mate with wild mosquitoes, they pass Wolbachia on to the next generation. Over time, the share of Wolbachia mosquitoes will grow, and these mosquitoes will also have reduced ability to transmit viruses to humans. The Wolbachia method is considered by WHO experts as a "promising new tool" to control the mosquito population.23Legend symbol denoting See World Health Organization (2016). Various places have shown an interest in this innovative method. Queensland of Australia has experimented with it since 2011; Guangzhou has launched a Wolbachia mosquito release project on two islands several years ago, successfully reducing the wild Aedes population by a whopping 83%-94%.24Legend symbol denoting This research considered the Wolbachia method cost-effective compared with traditional mosquito control strategies, with costs estimated at US$108-US$163 (HK$841-HK$1,269) per hectare annually. See Nature (2019), International Atomic Energy Agency (2019) and 廣東省人民政府(2019年). In Singapore, NEA has piloted Project Wolbachia, with phase one rolled out in 2016, to complement existing mosquito control strategies that rely on chemical use.25Legend symbol denoting NEA considers routine fogging unsustainable, as this has to be repeated frequently and has sparked concerns about excessive chemical use. See Today Online (2016) and National Environment Agency (2016). Estimated to cost S$1.24 million (HK$7.1 million) in 2020-202126Legend symbol denoting See Ministry of Finance (2021)., the NEA's project has the following features:

(a) Risk assessment: The adoption of novel technology is often not without controversy. To ease public concerns over Project Wolbachia, NEA has conducted comprehensive risk assessments and has determined the project to be safe, a conclusion that is consistent with trials conducted in places such as Australia and the United States.27Legend symbol denoting See National Environment Agency (2021c). According to NEA, releasing male Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes has negligible risk to human health as these male mosquitoes (unlike female ones) do not bite or transmit diseases; mosquitoes also make up a small percentage of the diet of predators like frogs, and thus the adverse impact on the local ecology should not be significant. (b) Phased approach: NEA has followed WHO's recommendation to conduct mosquito releases in stages, with rigorous monitoring and evaluation. Its trials started small at public housing estates with high mosquito populations and/or dengue outbreaks since 2016, and has gradually expanded to cover 1 000 housing blocks (where a total of some 98 000 households reside) in 2021.28Legend symbol denoting See National Environment Agency (2021d). As at July 2021, Singapore observed up to 98% suppression of Aedes mosquito population and 88% fewer dengue cases at the study sites.29Legend symbol denoting Ibid. (c) Public-private collaboration: The field trials have been enabled by NEA's collaboration with external partners. For example, NEA has worked with technology firms and research institutes to develop solutions for mass breeding and counting of Wolbachia mosquitoes, and explore the use of vans equipped with automation technology to conduct larger-scale releases. Five intellectual property patents have been filed as a result of these innovations.30Legend symbol denoting See National Environment Agency (2019).

Raising public awareness of and participation in mosquito prevention

- Promoting community awareness and engagement is considered conducive to more effective implementation and management of mosquito prevention and control measures. For example:

(a) Reaching out to the public via multiple channels: As mentioned above, both Beijing and Singapore disseminate information on mosquito warning via various channels. These can range from television programmes and websites to social media and mobile apps. Moreover, New South Wales of Australia has piloted a free SMS programme to provide other mosquito-related information in seven regions with a total population of around 300 000. During humid days in the mosquito season in February-April 2021 (i.e. summer and autumn months in Australia), participants not only received text and video messages with mosquito prevention reminders and tips, but also an education pack including a mosquito repellent to raise their awareness of mosquito-borne diseases. (b) Public participation in scientific process ("citizen science"): As mentioned above, Queensland has since 2011 been controlling mosquito growth with the Wolbachia method. It has funded Wolbachia trials in dengue-prone regions in tropical north Queensland, amongst other mosquito control efforts.31Legend symbol denoting These range from traditional methods like chemical application and removal of mosquito breeding sites, to newer methods such as developing a thin film on the water surface to prevent mosquitoes from laying eggs. See Queensland Health (2015). To increase public acceptance of the novel approach, the health authorities have engaged residents through comprehensive surveys, letters, door-knocking and even community mosquito releases. In 2019, Townsville, one of the trial regions, recruited 400 volunteers to host mosquito release containers and track progress of the project.32Legend symbol denoting Following an information session for participants, each volunteer received a container with Wolbachia-infected mosquito eggs, which would hatch into Wolbachia mosquitoes for release into the wild; some also helped at monitoring stations to track the spread of the released mosquito strain. The Wolbachia project in Townsville saw a public acceptance rate of 92%, with no local dengue transmission recorded in rainy seasons after the project's roll out.33Legend symbol denoting See World Mosquito Programme (2021b).

Following global Zika outbreaks in 2016, the Queensland government has also introduced the "Zika Mozzie Seeker" project to enlist public help in detecting Zika-transmitting mosquitoes. Participants receive a free kit with instructions on setting up backyard mosquito egg traps, which they then return to scientists for rapid DNA screening to confirm the presence of Aedes mosquitoes. Entering its ninth round in 2021, the project has involved nearly 3 000 participants, resulting in the testing of 170 000 mosquito eggs as at 2019.34Legend symbol denoting See Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2019). The government noted in a report that the project had helped achieve the dual goal of enabling unprecedented mass data collection of invasive mosquitoes while promoting active community participation in mosquito control work.35Legend symbol denoting See Office of the Queensland Chief Scientist (2018)..

Concluding remarks

- The growing impact of climate change on mosquito habitats and disease spread as well as concern over the use of chemical insecticides have warranted some places to rethink their mosquito prevention and control strategies. Selected cities on the Mainland and Singapore have managed to enhance mosquito surveillance with technology such as drones and artificial intelligence, and have also experimented with novel technologies such as infecting mosquitoes with bacteria to achieve over 90% reduction in Aedes mosquito population. Meanwhile, Australia has tapped into citizen science and various community programmes in an attempt to fortify mosquito control and gain wider support for such efforts. While these places are grappling with varying degree of mosquito infestations, their experience might provide inspirations and lessons for Hong Kong in seeking viable and sustainable anti-mosquito solutions.

Prepared by Jennifer LO

Research Office

Information Services Division

Legislative Council Secretariat

15 October 2021

Endnotes:

References:

| Hong Kong

| |

| 1. | Centre for Health Protection. (2019) Prevention of Mosquito-borne Diseases.

|

| 2. | Centre for Health Protection. (2021) Number of Notifiable Infectious Diseases by Month.

|

| 3. | Food and Environmental Hygiene Department. (2021a) Monthly Dengue Vector Surveillance.

|

| 4. | Food and Environmental Hygiene Department. (2021b) Vector-borne Diseases.

|

| 5. | Food and Health Bureau. (2021) Enhancement of Control Work of Mosquito and Biting Midge Infestation. LC Paper No. CB(2)1004/20-21(04).

|

| 6. | GovHK. (2016) LCQ20: Measures to Prevent Zika Virus Infection.

|

| 7. | GovHK. (2018) LCQ1: Prevention and Control of Mosquito and Rodent Problems.

|

| 8. | Legislative Council Secretariat. (2020) Administration's Mosquito Control Work. LC Paper No. CB(2)592/19-20(04).

|

| 9. | Office of the Ombudsman. (2021) Direct Investigation Report on Effectiveness of Mosquito Prevention and Control by Food and Environmental Hygiene Department.

|

| 10. | The University of Hong Kong. (2020) HKU Marine Ecologists Reveal Larvicidal Oil for Mosquito Control Threatens Coastal Marine Life and Pollutes Sea Environment.

|

| 11. | 《東方日報》: 政府滅蚊不力 登革熱爆疫,2018年8月24日。

|

| 12. | 食物環境衞生署:宣傳教育,2021年。

|

| 13. | 《香港01》: 香港蚊患嚴重 應否引入「太監蚊」 實行「以蚊制蚊」?,2018年8月17日。

|

| Global

| |

| 14. | World Health Organization. (2015) Innovation to Impact – WHO Change Plan for Strengthening Innovation, Quality and Use of Vector-control Tools.

|

| 15. | World Health Organization. (2016) Promising New Tools to Fight Aedes Mosquitoes.

|

| 16. | World Health Organization. (2021) Dengue and Severe Dengue.

|

| 17. | World Mosquito Programme. (2021a) Mosquito-borne Diseases.

|

| Australia

| |

| 18. | Queensland Health. (2015) Queensland Dengue Management Plan 2015-2020.

|

| 19. | Office of the Queensland Chief Scientist. (2018) Queensland Citizen Science Strategy.

|

| 20. | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019) Embracing Innovation in Government: Global Trends 2019.

|

| 21. | World Mosquito Programme. (2021b) Global Progress - Australia.

|

| The Mainland

| |

| 22. | Nature. (2019) World's Most Invasive Mosquito Nearly Eradicated from Two Islands in China.

|

| 23. | International Atomic Energy Agency. (2019) Mosquito Population Successfully Suppressed Through Pilot Study Using Nuclear Technique in China.

|

| 24. | 《央視網》: "蚊蟲叮咬指數"預報來了:為何預報?怎麼預報?如何防護?,2021年。

|

| 25. | 《新華網》: 北京首次發佈 "蚊蟲叮咬指數",2021年。

|

| 26. | 廣東省人民政府: "蚊子工廠"每週可生產1000萬隻蚊子 "以蚊滅蚊"已在廣州城區多處試點,2019年。

|

| Singapore

| |

| 27. | GovLab. (2016) Singapore's Dengue Cluster Map: Open Data for Public Health.

|

| 28. | Ministry of Finance. (2021) Singapore Budget 2021.

|

| 29. | Ministry of Transport. (2016) Use of Unmanned Aircraft Systems in Dengue Control Operations.

|

| 30. | National Environment Agency. (2016) Why Can't NEA Just Fog the Entire Island to Kill Adult Mosquitoes?

|

| 31. | National Environment Agency. (2019) NEA Urges Heightened Vigilance as Dengue Cases Spike.

|

| 32. | National Environment Agency. (2020) NEA to Impose Heavier Penalties from 15 July 2020 for Households Found with Repeated Mosquito Breeding Offences and Multiple Mosquito Breeding Habitats.

|

| 33. | National Environment Agency. (2021a) NEA Urges Continued Vigilance at Start of 2021 as Aedes Aegypti Mosquito Population Remains High and Many Residents Continue to Work from Home.

|

| 34. | National Environment Agency. (2021b) NEA Urges Vigilance as Aedes Aegypti Mosquito Population Remains High in Residential Areas.

|

| 35. | National Environment Agency. (2021c) Wolbachia is Safe and Natural.

|

| 36. | National Environment Agency. (2021d) Wolbachia-Aedes Suppression Technology - Frequently Asked Questions.

|

| 37. | Today Online. (2016) Eradicating the Source Key to Fighting Dengue, Zika in Long Run: Masagos.

|

Essentials are compiled for Members and Committees of the Legislative Council. They are not legal or other professional advice and shall not be relied on as such. Essentials are subject to copyright owned by The Legislative Council Commission (The Commission). The Commission permits accurate reproduction of Essentials for non-commercial use in a manner not adversely affecting the Legislative Council. Please refer to the Disclaimer and Copyright Notice on the Legislative Council website at www.legco.gov.hk for details. The paper number of this issue of Essentials is ISE32/20-21.

Quick Links

The LegCo

LegCo at Work

Public Engagement

- Invitation for Submission

- Webcast

- Security screening arrangements for admission to the Legislative Council Complex

- Observing Council and Committee Meetings

- Note for the public attending or observing meetings

- Guidelines for staging petitions or demonstrations

- Education

- Visiting and Guided Tours

- Virtual tour of LegCo Complex

- Souvenir Shop

- Flickr

- YouTube

- LegCo Mobile App

Useful Information

About This Website

Disclaimer and Copyright Notice | Privacy Policy | © Copyright 2022 The Legislative Council Commission

Share this page

Share this page